The Little Rebel: BreakING from Kamasan Tradition

In a storm a tiger, a monkey, a snake, and a goldsmith are swept into a well. Fortunately, a priest named Dharmaswami comes across the well and rescues them.

KAMASAN ART

The artisans of East Java's Majapahit Empire, from the 13th to the 16th centuries, crafted a style of painting that found its way to Bali in the late 13th century. By the 16th century, the village of Kamasan in Klungkung became the heart of classical Balinese art, birthing what we now call Kamasan paintings.

The origin of Kamasan painting is based on the expansion from the painting on lontar leaves, which indicates the subject of wong-wongan (humans). This art form reached the golden age when Bali was ordered by the king of Dalem Waturenggong (1386-1460). In the 18th century, a talented artist named Mudara, whose real name was Gede Marsadi (1771 AD), emerged. His exceptional ability in wayang painting became well-known when the King of Klungkung I Dewa Agung Made assigned him to create a picture of Patih Mudara from the Boma lontar story. The resulting painting was so impressive that the king always called Gede Marsadi "Mudara." Then the style of Mudara painting was imitated by many artists across Bali, and the form and pattern of Mudara became the identity of wayang painting in Kamasan Village. In its development, this painting art became known as Wayang Kamasan Painting.

These paintings were often a communal effort. The master artist set the stage, sketching the details and outlines, while apprentices filled in the colors. These works were more than mere art; they were a collective expression of the village's values and gratitude to the Divine. The colors came from nature: iron oxide stone for brown, pig bones for white, ocher oxide clay for yellow, indigo leaves for blue, and carbon soot or ink for black.

Kamasan paintings, detailed and narrative, held a crucial place in Balinese culture. They bridged the material world and the realm of the divine and demonic. The artist was a medium, translating the unseen into a visual language that made sense of life's mysteries. These two-dimensional works depicted three levels: the upper realm of gods and benevolent deities, the middle realm of kings and aristocracy, and the lower realm of humans and demonic forces. Details in facial features, costumes, body size, and skin color marked the rank and character type. Darker skin and large bodies belonged to ogres; light skin and finely portioned bodies belonged to gods and kings. Strict rules governed the depiction of forms—three or four types of eyes, five or six different postures, and specific headdresses. The position of hands conveyed questions, answers, commands, and obedience.

The stories in these paintings came from Hindu and Buddhist texts like the Ramayana, Mahabharata, Sutasoma, and Tantri, as well as Javanese-Balinese folktales and romances like Panji. Astrological, earthquake, and birth charts also found a place in the art. Major mythological themes were rendered with great symmetry, teaching high moral standards and virtues to encourage peace and harmony. A beautiful painting communicated balance, both aesthetically and metaphorically, signifying the artist's union with the divine.

Kamasan painting is not static; it evolves. Each artist brings subtle changes in style, composition, and color. New works regularly replace the old and damaged ones, keeping Kamasan painting an authentic, living Balinese tradition.

THE PITA MAHA GROUP

By the early 20th century, the pictorial tradition in Bali had become largely uniform, with its iconography remaining consistent since the 16th century. The modern evolution of Balinese art is often linked to the arrival of Walter Spies on the island. In January 1936, Spies co-founded Pita Maha (The Great Light), an association of local artists aimed at refining painting techniques. Spies encouraged his students to break free from the constraints of traditional Balinese mythological themes and explore depictions of everyday life. Pita Maha's influence spread across Bali, blending local art with Western influences and giving rise to new characteristics in traditional Balinese art. By the 1930s, this movement had led to a fresh style of visual expression and marked the beginning of modern Balinese art schools.

Sketching & ink outlines

Outlining process

Dharmaswami ( The Priest Frees Monkey, Tiger, And Snake From Wel).

49 x 67CM, 2023, By Deknoo Adnyana Dass , after Ida Bagus Gelgel.

Sketching & ink outlines

Painting process

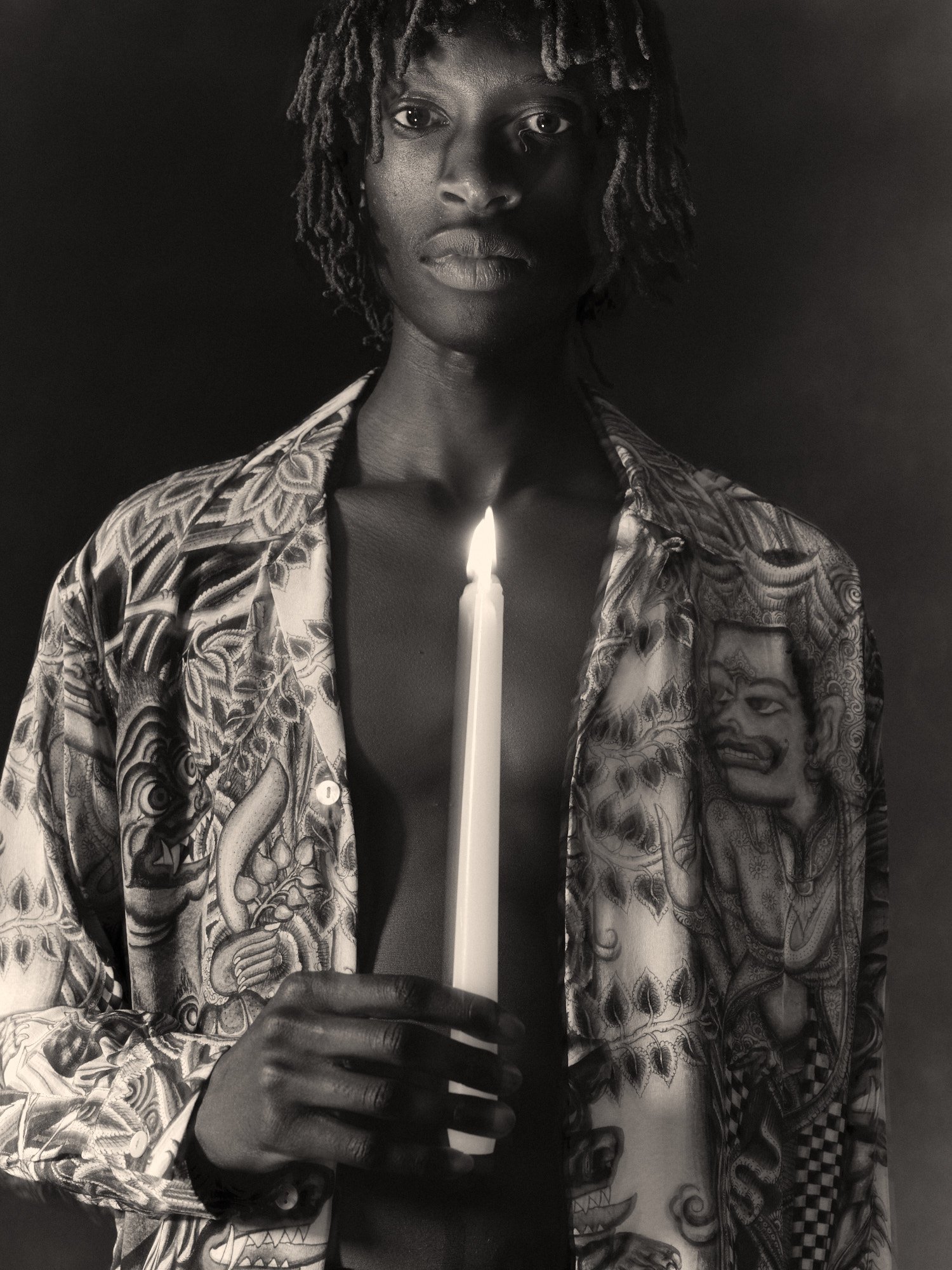

Deknoo Adnyana Dass

THE LITTLE REBEL

The painting "Ib Gelgel, The Priest Frees Monkey, Tiger, And Snake From Well" from 1930 presents a challenge in categorisation. Whist the artwork is considered a masterpiece from the golden age of the pita maha group, it draws influence from tradition Kamasan painting as a primary resource for visual language. What set this artwork aside is the execution process, which deviates significantly from the established norms of Kamasan painting.

It is essential to acknowledge that Kamasan painting is considered classical due to its adherence to ‘uger-uger’ stringent rules that have been preserved across generations. Typically, Kamasan paintings depict the tri loka and employ a hierarchical composition that delineates the world into lower, middle, and upper realms. The lower tier typically features animal depictions, the middle comprises human representations, and the upper tier embodies deities or semi-deities.

Gelgel's oeuvre reflects his endeavour to dismantle the prevalent hierarchical structure of Kamasan paintings during his era. The distinctiveness of Gelgel's paintings emanates from his deliberate selection of narratives and epics, with the majority of his works portraying the essence of life and simplicity. Reflecting his unassuming and pure disposition, Gelgel, originating from a modest background of farmers and labourers, embraced elevated spiritual principles. Gelgel was nicknamed 'little rebel' due to his efforts to challenge the norms in Kamasan painting.

THE PRIEST FREES MONKEY, TIGER, AND SNAKE FROM WELL

In a storm a tiger, a monkey, a snake, and a goldsmith are swept into a well. Fortunately, a priest named Dharmaswami comes across the well and rescues them. The animals caution the priest against aiding the goldsmith, attributing their misfortune to him. Despite the advice, Dharmaswami, as a guardian of virtue, extends his help to the goldsmith. In gratitude, the animals present the priest with gifts: fruits from the monkey, and gold jewelry from the tiger. Dharmaswami, in turn, gives the jewels to the goldsmith.

However, trouble ensues when the goldsmith identifies the jewelry as belonging to a prince. He accuses Dharmaswami of murder, leading to the priest's arrest and torture. Learning of his dire situation, the animal friends intervene; the tiger wreaks havoc, and the snake bites a prince, causing a severe illness. The snake then transforms into a divine figure, asserting that only Dharmaswami can provide the antidote. The priest successfully saves the young prince.

In the end, justice prevails as the false accusations result in punishment for the goldsmith. The narrative highlights animals' profound gratitude compared to humans. The accompanying painting depicts the rescued animals expressing their gratitude to the priest and presenting him with their gifts after their escape from the well.

Artwork Ida Bagus Gelgel, faithfully recreated By Deknoo Adnyana Dass.

With many thanks to Ida Bagus Rekha Bayutha and the estate of Ida Bagus Gelgel.